Corporations spend billions of dollars each year to train and develop their employees, yet post-training surveys tell us that a majority of trainees who participate in a typical corporate training program do not effectively use their new skills and capabilities on the job.

Researchers point to a number of reasons why training programs fail to take root in the corporate environment, including lack of reinforcement and practice, the training content or modality itself, ineffective instruction, or too little time spent on understanding employee training needs. In fact, many training professionals believe that technology is the answer to the problem. Online learning, mobile applications, computer simulations, video training and distance learning are all prominent methodologies in many corporate learning cultures meant to make training more effective and accessible.

It is not that these factors have nothing to do with learning success or that these technical applications should be abandoned. There is no argument that all of these factors have an impact on employee learning. However, the focus of this article is to discuss a critical factor that has been missing when explaining the shortcomings of our corporate training programs.

Worldwide, companies are becoming aware of the link between employee development and cognitive ability. In many cases, they are discovering that learning failure is not due entirely to the multitude of factors we so often hear about, but rather it is the failure of the organization to use what is known about positive adult development and stage change to improve the employee’s chances of fully comprehending and applying what they have learned.

Stage Development

In 1954, Jean Piaget introduced the idea that child development proceeds in discrete stages. These stages encompass sequential periods in the growth or maturating of an individual’s ability to think, to gain knowledge, self-awareness, and awareness of the environment. Since the days of Piaget, multiple models have been presented to conceptualize stage development in adults as well. In the Model of Hierarchical Complexity (MHC) developed by Commons and Richards (1998), performance is examined as a series of steps in a dynamic transition process.

The MHC is a cross-domain, or universal system that classifies the task-required hierarchical organization of responses. In order for one task to be more hierarchically complex than another, the new task must meet three requirements:

- It must be defined in terms of the lower stage actions

- It must coordinate the lower stage actions

- It must do so in a non-arbitrary way

Research related to the MHC tells us that there are minimal sequences of behavioral developmental stages at which both learning and teaching take place. Two questions must be answered in order to improve employee learning and development:

- What is the actual performance stage of the organization, the tasks and the employee?

- What are the motivational conditions necessary to support the transition between stages

Hierarchical analysis of a task and the employee’s performance on that task yields a distinct developmental stage that is defined as the highest order hierarchical complexity of the task performed or solved. In other words, the complexity of a given task predicts stage performance if that task is completed correctly. Therefore, if the learning or job task being taught is more hierarchically complex than the employee’s current stage, it may have no effect at all on the employee’s performance. That means the necessary learning did not occur.

Not only did learning not take place for this employee but now they may face other psychological impacts such as increased anxiety, resistance and fear that will present barriers to their motivation for learning and completing the task. The MHC tells us that people who are confronted with tasks that are two or more stages above where they are currently functioning will fail, even with the best of instruction.

As a matter of fact, it may also be the case that organizations and institutions punish higher-stage performances by limiting opportunities for innovation, not listening to employees, dismissing employee ideas and suggestions, and/or failing to engage employees in the overall goals and objectives of the company. This type of punishment usually decreases the inclination of the employee to engage at a higher level of reasoning and therefore maintains or even increases the avoidance of transitioning to higher stage behaviors.

Identifying Talent

Corporations are charged with identifying the organizational capabilities and talent that they will need in order to achieve business goals and objectives. In addition, they must look ahead to assess what they will need to win the marketplace over the next 36 to 48 months. More and more businesses demand a “higher standard” of performance from their employees. The competitive marketplace is getting more and more complex. Money is spent recruiting, training, assessing and accelerating the development of employees to meet these rising standards with little to no success.

Managers also assume that as additional tasks are added to a job position in the way of new products, new skills, increased job complexity, etc., the employees will learn these tasks through the use of training programs, job aids, manuals or other established methods. Once again, if these skills and/or tasks are two or more stages above where the employee is currently functioning, sufficient learning will not occur.

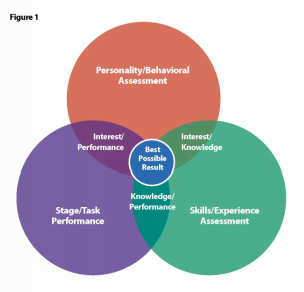

For example, companies typically have a list of discrete job responsibilities that are specified for each employee position. Each responsibility represents a task, or a set of tasks. Without a measure of hierarchical complexity, managers will fill their job vacancies by reviewing a resume to determine what the candidate has accomplished in the past. It is also quite common today for managers to require the candidate to take a skills test and perhaps even a personality inventory such as the DISC or the Predictive Index. These assessments can help determine if the candidate possesses the required skills for performing the job, predicting how well one is suited to the job and how well they will enjoy performing the tasks, but that alone does not tell the entire story.

Figure 1 shows the third critical element in assessing an employee’s ability to successfully complete the tasks and responsibilities of their job: stage/task performance. It is important to note that complexity is not the same thing as one’s “intelligence.” Over the years, intelligence has been understood theoretically as single general ability factor greatly influenced by one’s genetics and thus not subject to change. Hierarchical complexity is best described as one’s ability to resolve complex problems. Because this ability is primarily developed through experience and learning everyone had the potential to transition and grow.

Figure 1 shows the third critical element in assessing an employee’s ability to successfully complete the tasks and responsibilities of their job: stage/task performance. It is important to note that complexity is not the same thing as one’s “intelligence.” Over the years, intelligence has been understood theoretically as single general ability factor greatly influenced by one’s genetics and thus not subject to change. Hierarchical complexity is best described as one’s ability to resolve complex problems. Because this ability is primarily developed through experience and learning everyone had the potential to transition and grow.

Unfortunately, rather than focus on what can be done to transition from one stage to the next, our society has a tendency to simplify the environment to fit the current stage of hierarchical complexity. For example, criteria for a passing grade or skill certification may be reduced over time when lower-stage individuals are more prevalent in the environment. However, with the right preparation, experiences and support, a stage change is possible that will allow the employee to learn and apply new skills.

Stage has an enormous impact in the world and in the workplace. By understanding stages of complexity, leaders will understand where intervention is necessary within their organizations and what interventions work at each stage. Over time with the use of scores that represent changes in stage, one can discover what role each level plays in producing behavior change and whether it is helping or hindering the change needed to progress within and between stages.

The good news is that scientific tools are making their way into the workplace to help businesses measure how well an applicant or employee will perform on the job and how well they deal with the ever growing complexity of the workplace.

Commons, M.L.; Robinett, T.L. (2013) Adult Development: Predicting Learning Success